Friday, December 17, 2010

Iced!

An arctic blast whipped up the winds on Lake Erie, encasing Cleveland Harbor Ledge Light in ice. Here's an AP video--sit through the ad; it's worth it.

Saturday, November 27, 2010

New Northwest Lighthouses Map & Guide

Our newly redesigned and revised Northwest Lighthouses Map & Guide is available.

Coming to shops in Oregon, Washington and Alaska, and available now from amazon.com.

Retailers: Contact us for information on how to stock it!

Retailers: Contact us for information on how to stock it!

Coming to shops in Oregon, Washington and Alaska, and available now from amazon.com.

Retailers: Contact us for information on how to stock it!

Retailers: Contact us for information on how to stock it!

Thursday, October 14, 2010

Thursday, October 7, 2010

Cape Meares Lighthouse, Oregon

Walking down the path to Cape Meares lighthouse, it became clear how vandals were able to do so much damage to the lantern room and Fresnel lens earlier this year. It's still a great one to visit, really cute, and in a great setting.

Views from the lighthouse:

Tuesday, September 21, 2010

News from 1938: HURRICANE!

Damaged homes on Long Island, courtesy SUNY Suffolk.

The New England Hurricane of 1938 (aka the "Long Island Express") hit on Sept. 21, with a storm surge made even more powerful by the equinox and full moon. Some 700 people were killed between eastern Long Island and Massachusetts; property damage was estimated at $306 million ($4.72 billion in today's dollars), including half of the Northeast apple crop.

From the New York Times, Sept. 22:

From the US Coast Guard:Storm Batters All New England;

Providence Hit by Tidal Wave

Six Feet of Water in Streets of Business Section--Many Homeless in Area

Woonsocket Also Suffers

BOSTON, Sept. 21.--A terrific wind, touching 100-mile-an-hour hurricane force, tonight swept across New England, lashing sea water high into the streets of coastal cities, causing at least eighty known deaths and hundreds of injuries and resulting in damages reaching into tens of millions of dollars.

Sept. 21, 1938--A hurricane hit the northeast coast, wreaking havoc among the lighthouses and the light keepers there. First assistant keeper Walter B. Eberle of the Whale Rock [RI] light was killed when his lighthouse was swept into the sea. The wife of head keeper Arthur A. Small was killed when she was swept away from the Palmer Island [MA] Light Station. The keeper of the Prudence Island [RI] Light Station's wife and son were drowned when that light station was swept into the sea. Many more stations and depots were severely damaged as well.

Watch this newsreel about the massive destruction and WPA's relief work:

Thursday, September 16, 2010

104 Years Ago Today: Steamship Wreck in Alaska

The U.S. Lighthouse Service tender Armeria, assigned to Ketchikan, Alaska, ran aground off Cape Hinchinbrook on 20 May 1912 while delivering supplies for the Cape Hinchinbrook lighthouse. Courtesy US Coast Guard.

The U.S. Lighthouse Service tender Armeria, assigned to Ketchikan, Alaska, ran aground off Cape Hinchinbrook on 20 May 1912 while delivering supplies for the Cape Hinchinbrook lighthouse. Courtesy US Coast Guard.From the New York Times, Sept. 16, 1906:

ALL SAFE OFF THE OREGON.;

Passengers Take to Life Boats and Are Picked Up -- Steamer Doomed.

Passengers Take to Life Boats and Are Picked Up -- Steamer Doomed.

VALDEZ, Alaska, Sept. 15. -- Passengers and seamen of the steamer Oregon, which ran on the rocks at Hinchinbrook Island on Thursday night, took to the lifeboats the morning after the steamship struck, and were picked up several hours later by the lighthouse tender Columbine, which was surveying those waters for the lighthouse on Hinchinbrook.

The Columbine arrived at Valdez with the passengers and mail this morning. The revenue cutters sent to the wreck have not returned. The Oregon was three miles off her course east of Hinchinbrook and struck the rocks fifty yards from shore, where the bank is perpendicular. There was no chance to land. She slid off until she listed in a few feet of water with several fathoms under the stern. She is hard and fast aground, filled with water to the second deck, and probably will go to pieces in the first good swell from the ocean.

The Captain maintained good discipline and threatened to shoot men who were attempting to get off in a a lifeboat, after which his orders were obeyed without question, and all got off without accident.

If the weather remains calm there is a possible chance of lightening some of the Oregon’s cargo, but as the boat is on the ocean side of the island, exposed to the swell, such salvage is doubtful.

Tuesday, September 14, 2010

112-Year-Old News: Rescue in Alaska

Icebound in Alaska by AJ Fuller, from Jaws Marine.

Icebound in Alaska by AJ Fuller, from Jaws Marine.Look what we found while researching the lost lighthouse at Point Hope, Alaska--more than 100 miles north of the Arctic Circle and one of the oldest continuously inhabited sites in North America.

From the New York Times, Sept. 14, 1898:

THE BEAR SAVES WHALERS

Revenue Cutter Rescues 116 Men from the Vessels

Crushed Off Point Barrow.

CAUGHT IN THE ICE FLOES

Government Vessel Unable to Move Through the Frozen Seas

for Thirteen Days—On Her Way South.

Revenue Cutter Rescues 116 Men from the Vessels

Crushed Off Point Barrow.

CAUGHT IN THE ICE FLOES

Government Vessel Unable to Move Through the Frozen Seas

for Thirteen Days—On Her Way South.

ST. MICHAEL, Aug. 26.—The revenue cutter Bear arrived in port this afternoon with 116 whalers belonging to vessels of the fleet that was crushed in the ice pack while in Winter quarters off Point Barrow on July 28, the first vessel of the season to arrive. She found the surviving members of the steamers Orca and Jessie H. Freeman and the schooner Rosario, and took them on board, giving them the first full meal they had enjoyed in many days.

The rescuing party found that provisions on the Belvidere, Newport, Jeannette, and Fearless, the vessels which escaped destruction in the ice floes, were getting low. Each vessel was supplied with sufficient until the arrival of tenders from the South.

On Aug. 17, having fulfilled her mission of rescue and relief, the Bear started South on her journey to St. Michael with the 116 whalers whose ships were lost. Shortly after her arrival at Point Barrow the Bear was caught in the ice, and the pressure was so tremendous that some of her planks started, and preparations were made for abandoning the ship. Fortunately the pressure subsided, but the Bear was unable to free herself from the pack for thirteen days after first being pinched.

The Bear left St. Michael for the north on July 5, to rescue nine miners whose boat, a large steam launch, had been wrecked five miles south of Cape Ramanoff, while making the trip from Rampart City, on the Yukon River, to St. Michael, for provisions and supplies. All the miners were saved and the Bear proceeded on her way to Point Barrow. On the way several stops were made, and bills contracted by Lieut. Jarvis of the overland relief expedition were paid in goods wanted by the natives. At Point Hope, Lieut. Bertholf reported that the thirty-four reindeer which had strayed from the Laps’ herd while crossing Kotzebue Sound on the way to Point Barrow, had been brought back to Point Hope, and, although several had been killed for food, the herd had increased by the birth of fawns to forty-nine.

Capt. Sherman of the wrecked whaler Orca boarded the Bear at Point Day. He reported the wreck of the Rosario and the serious condition of the Belvidere. It being impossible for the Bear to pass the ice barrier, food was sent to the Belvidere’s men by a native in skin boats in charge of Lieut. Hamlet, who successfully accomplished his mission and reached Point Barrow only eighteen hours after the Bear’s arrival there.

The Newport, Fearless, and Jeannette arrived before Aug. 3, when the Bear became fast in the ice, where she remained for thirteen days, it being found impossible to blast her way out. Stores were, however, transferred to the whalers on sleds. Finally, on Aug. 17, the Bear got loose from the ice, and with the rescued whalers started on her way south. A stop was made at Point Hope on the 20th, where the schooner Louise J. Kinney was found on the beach, where she had been wrecked the day before. Her officers and crew were taken on board. After making several stops the Bear arrived at St. Michael on Aug. 25 and left on the following day.

Monday, September 13, 2010

99 Years Ago Today: Shipwreck in Alaska

Surf roars over Cape Decision, courtesy of NOAA.

Surf roars over Cape Decision, courtesy of NOAA.SAVED FROM ALASKA WRECK.;

Fishermen Rescue Thirty Passengers on Sinking Steamship Ramona.

SEATTLE, Sept. 12. -- A brief wireless message received here to-day tells of the loss of the steamer Ramona, which struck the rocks near Cape Decision in Frederick Sound, about 200 mi this side of Ketchikan, Alaska, late Sunday, in a dense fog, and was slowly pounded to pieces. Fishermen Rescue Thirty Passengers on Sinking Steamship Ramona.

Wireless messages sent out for hours by the Ramona were finally picked up, and the crack liner of the Alaska Steamship Company, the Northwestern, Capt. J.C. Hunter, took aboard the passengers and crew.

The Ramona is a total loss. The Ramona had a long list of first-class passengers, including many Eastern tourists. She was proceeding to Seattle via the dangerous inside passage. The Pacific Coast Company officials, owners of the Ramona, are unable to tell who was on board, and will not know until the ship’s records are received here.

The Northwestern had passed the scene of the wreck, which is quite out of the beaten path. Local marine men marvel at Capt. Hunter’s feat of turning the big Northwestern around in the dangerous inside passage and picking his way back to the wreck.

This is the third steamer the Pacific Coast Company has lost this season.

The passengers of the Ramona, who barely escaped with their lives, so speedily did the ship sink, saved nothing but the clothing they wore. Thirty of the passengers and crew were picked up by the fishing steamer Grant. The remainder landed on Spanish Island, which is timbered but uninhabited, and remained there a day and a night. The freight steamer Delhi came along, and the ship-wrecked voyagers rowed out to the Delhi and were taken aboard. Subsequently the Northwestern took the passengers from the Grant and the Delhi, and all are on their way to Seattle.

The Ramona left Skagway Sept. 8, and was calling at the various canneries to take passengers and freight. The vessel was valued at $200,000.

Cape Decision Lighthouse, by Tuggerdave

Cape Decision Lighthouse, by TuggerdaveFriday, September 3, 2010

August visit to Maine

Our publisher and her Mostly Silent Partner had an enjoyable visit to Maine a couple of weeks ago.

First stop was Cape Neddick lighthouse. Since our visit last year, the lovely gift shop the Town of York operates near the light has become one of our most successful dealers.

We of course visited Lighthouse Depot and the wonderful DeLorme Map Store, two other valued dealers for our lighthouse maps.

Here are photos we took of three other lighthouses on this trip:

First stop was Cape Neddick lighthouse. Since our visit last year, the lovely gift shop the Town of York operates near the light has become one of our most successful dealers.

We of course visited Lighthouse Depot and the wonderful DeLorme Map Store, two other valued dealers for our lighthouse maps.

Here are photos we took of three other lighthouses on this trip:

SPRING POINT LEDGE

This lighthouse is at the end of a breakwater in South Portland Maine. We enjoyed brunch at Joe's Boathouse at the nearby marina and took in these views:

PORTLAND BREAKWATER (BUG LIGHT)

Located a short walk from Spring Point, this cute lighthouse is now located in a small park. We arrived at the end of a tugboat race in a light rain.

Monday, July 12, 2010

Sea Monster on the Umpqua River!

While researching the Umpqua River Lighthouse for our forthcoming Northwest Lighthouses map, we found this delightful tidbit from October 28, 1888, in the New York Times archives:

THE SEA SERPENT AGAIN.

From the San Francisco Alta, Oct. 12.

The regular annual sea serpent has made his appearance again. He is a little out of his latitude this time, having been seen in a place where heretofore he has never been known to roam. There is no doubt as to the identity of the creature, as it is vouched for by several parties who are known as strictly temperate men, whose eyes have not been accustomed to seeing every variety of snakes floating in the air and in every conceivable position. Capt. Edgar Avery of the bark Estrella, while coming from Tacoma to this city with coal, descried the monster when the bark was passing the Umpqua River. The serpent, for such the Captain solemnly declares it to be, was swimming on the surface of the water in a southerly direction. The bark at the time was headed south-southeast, and when the Captain first noticed the reptile it was about 200 yards off, and was apparently not the least disconcerted by the proximity of the vessel. As it was 10 o’clock in the morning, and the sun was shining brightly, the startled Captain had a good view of the serpent. When he was satisfied that he beheld a real live serpent, and not a creation of his imagination, the Captain sprang below and got his rifle, calling to his wife and crew to come on deck and view the wonder. The lady and several of the crew came on deck and plainly saw the monster swimming by. He appeared to be about 80 feet long and as big round as a barrel. He rode over the waves with his head and about 10 feet of his body elevated above water, every now and then dipping his immense head into the water, the body making gigantic convolutions while gliding caterpillar-like over the waves. The head was flat, or “dished,” as the Captain described it, and the body appeared to be covered with scales. About 10 feet of what might properly be called the neck, was covered with coarse hair, resembling a mane. After viewing the monster for a time, the Captain raised his rifle and fired several shots at it, but the bullets fell short. The sea serpent seemingly paid no attention to the shooting, but kept on his way. The excited spectators kept it in view for fully a half hour, when, without any apparent flurry, it sank out of sight in the sea, and was not seen after.

Monday, July 5, 2010

"Terrible Tilly"

Tillamook Rock Light, by Gary D. Moon. Source: City of Cannon Beach.

Tillamook Rock Light, by Gary D. Moon. Source: City of Cannon Beach.After more than two years of arduous construction, during which a supervisor was drowned, Tillamook Rock, Oregon, went into service on January 21, 1881. Two weeks before, The New York Times reported these stories:

San Francisco, Jan. 7 – An Astoria dispatch says: “Wreckage is coming ashore on Clatsop Beach which indicates the total loss of the British ship Lupata. Buckets, barrel-heads, and other articles bearing the name ‘Lupata’ have come ashore. She is supposed to have gone to pieces near Tillamook Rock.”Lighthouse keepers, who had to be hauled up for duty via a breeches buoy, soon called the station "Terrible Tilly." A NYT report from 1894 shows why:

A SHIP'S WHOLE CREW LOST; WRECK OF THE BRITISH SHIP LUPATA ON THE PACIFIC COAST.

San Francisco, Jan. 8 – A dispatch from Astoria says: “By the arrival of the Lighthouse tender this evening from Tillamook Rock, the loss of the British ship Lupata is confirmed. Capt. Wheeler, Superintendent of the Tillamook rock Light-house, arrived here this evening, and reports that on Monday evening, Jan. 3, about 8 o’clock, the weather being very thick and the wind blowing hard from the south-west, the workmen on the rock suddenly heard loud voices shouting, and on emerging from their houses saw the ship’s light just inside of the rock, and immediately after heard the command given, “hard aport.” Capt. Wheeler ordered lanterns to be placed in tower, and as speedily as possible a large bonfire was started, which revealed a large vessel apparently not 200 yards from the east side of the rock, with a red or port light in sight about five minutes, when it gradually disappeared, those on the rock concluding that the Captain had backed ship and successfully steered his vessel out of danger. This morning the fog had disappeared and it was found that the Captain, instead of rounding the rock to the westward, had run his vessel ashore on the reef running out from the Tillamook side, the topmast being plainly visible from 6 to 10 feet above the water. The shore line being a bold bluff rock for a considerable distance from the scene of the wreck, it is more than likely that the whole ship’s company were lost.

The Wreck of the Tillamook Light.Still unimpressed? From a Dec. 26, 1897, NYT story on DESTRUCTIVE OCEAN WAVES:

WASHINGTON, Dec. 26 – Some details of the terrific storm on the Pacific coast, when the great lighthouse at Tillamook, Oregon, was wrecked, are contained in an official report received to-day by Capt. Wilde of the Lighthouse Board. The lighthouse is on a rock 91½ feet above high-water mark. The waves lashed the rock with such fury and violence that pieces weighing as much as 167 pounds were rent from its sides and hurled into the air about 140 feet, shattering thirteen panes of glass about the immense lens, and falling upon the wooden structures beneath, caving in the roof. The damage amounted to $1,200. A new light has been placed in position.

A few years ago a heavy gale swept along the Oregon coast raising a sea that broke completely over Tillamook Rock Lighthouse. The two boats kept on the rock were swept away. The platform where stores and visitors were landed, which was anchored to the rocks with iron bolts, was swept away, a steam boiler and engine bed were carried off, and the tramway, though bolted to the rock, was torn up and destroyed. A few days afterward the waves got up to such a tremendous height that salt water, not spray, but solid water, poured down the dome of the lantern situated 157 feet above sea level.From a July 6, 1902, NYT Magazine article on THE NEW "OCEAN GRAVEYARD":

Tillamook Rock is eighteen miles off the mouth of the Columbia River. There is a lighthouse on the rock which is called the high school of the Lighthouse Service. Two men have gone insane there from the loneliness and the peril of the elements. What happens occasionally to Tillamook will show just what a northwest storm can do. The rock is eighty feet above sea level, and water roundabout is ninety feet deep.And from 1934:

The house where the watchmen live is on the summit, and the light itself rises 136 feet above sea level. Yet during big storms the water often actually washes the plate glass of the light. Worse still, the keepers are compelled continually to be on the lookout for the rocks which are often hurled high above the island’s surface by the waves. The storm which sent the Lupata to the bottom was not the worst in the history of Tillamook. It is a fact vouched for by Chief Keeper Peronen that on Dec. 9, 1894, the waves broke off huge pieces of rock from the shore and hurled them high up against the light.

5 BESIEGED BY SEA IN LIGHTHOUSE SAVED; Boat Crew Shoots Line Over Oregon Coast Rock Where Men Were Held 6 Weeks.Tillamock Rock Light was deactivated in 1957 and eventually sold to be used as a columbarium (repository for human cremains). But as the Times reported in 2007, "the departed rest not quite in peace" because the columbarium owner's license was revoked and the lighthouse--now accessible only by helicopter--is succumbing to the elements and bird droppings.

ASTORIA, Ore., Dec. 2 (AP). – Delivered at last from a storm-besieged lighthouse in which they had been marooned six weeks, five men scurried to their homes today.

Their rescue was accomplished by the lighthouse tender Rose, which manoeuvred through treacherous seas to a point near Tillamook Rock Light, one mile off the Oregon shore. The crew of the Rose shot a line over the rock, set up a breeches buoy and removed the five.

Two hours were required to take off the five men and place two more on the half-acre rock. Two more hours were needed to land 1,500 pounds of fresh groceries and other supplies on the rock.

The men were brought here to recuperate from their illness. Most seriously ill were Henry Jenkins and E. La Schenger, who had been at the lighthouse for several months and twice had seen and heard the raging seas break waves which rolled up the sides of Tillamook Rock and completely over the 133-foot lantern tower.

The workers had been placed there to repair damage wrought six weeks ago by a storm which ripped away the regular landing derrick.

Monday, June 28, 2010

In the Limelight

South Foreland light, from Simplon Postcards.

South Foreland light, from Simplon Postcards.From the 1895 edition of Harper's Book of Facts: A Classified History of the World Embracing Science, Literature, and Art:

Lime-light, produced by burning hydrogen or carburetted hydrogen with oxygen on a surface of lime, evolving little heat and not vitiating the air. It is also called Drummond light, after lieut. Thomas Drummond, who successfully produced it in 1826, and employed it on the British Ordnance survey. It is said to have been seen 112 miles. It was tried at the South Foreland light-house in 1861. Lieut. Drummond was born 1797, died 15 Apr. 1840. To him is attributed the maxim that “property has its duties as well as its rights.”

Saturday, June 26, 2010

The Romance of Being a Lighthouse Keeper

Lighthouse and attached keeper's quarters that stood in Cleveland, OH.

The text below and illustration above are from “The Light-Houses of the United States” in Harper's New Monthly Magazine (Vol. 48, Dec. 1873 to May 1874):

Most of our light-houses are on barren, desolate, and exposed points of the coast. In some of them the keepers can not communicate at all with the shore during the winter months, and in such cases supplies of all kinds for the lights and the keepers must be accumulated beforehand. In many freshwater for the keeper and his family has to be caught in cisterns; and there is an official circular to light-keepers, telling them how to avoid the poisonous effect of the water dripping from the leads of the lighthouses by putting powdered chalk into the cistern, and occasionally stirring it. In many places it has been found that cattle, attracted to the light at night, destroyed the strong-rooted grass which holds down sand dunes, and thus exposed the light-house itself to destruction; and in such cases a considerable area of land must be fenced in to exclude these beasts. On stormy nights sea-fowl are apt to dash themselves against the lantern glasses, blinded probably by the glare of the lights, and all light-keepers are specially warned in their printed instructions to be on the watch for such an accident, and extra panes of glass, fixed in frames, are always in readiness in every light-house, to substitute for those which may thus be broken.

In fact, the Light-house Board carries on and provides for an infinite number of details, many of them petty, but none unimportant. It must provide oil for the lamps, and oil butts must be ingeniously contrived so as to exclude air from their contents. It must keep a store of wicks, and of lamp scissors to trim the wicks; it must provide the most durable and economical paint for the iron of the lanterns; it has to send on supplies of food; and for the more complicated lights of the higher orders it has not only to provide expensive machinery, but must also keep on hand delicate yet simple tests by the help of which the light-keeper may be able daily to see that his lamp is set in the exact plane, and his wicks are trimmed precisely high enough. It must provide such seemingly trifling articles as dusting and feather brushes, linen aprons, rouge powder, prepared whiting, spirits of wine, buff or chamois skins, and linen cleaning cloths, and what will appeal to the sensibilities of most country housekeepers, the Light-house Board must keep on hand at each light-house a sufficient supply of glass chimneys for the lamps. No doubt the board possesses the invaluable secret of making chimneys last a long time, and no doubt many an excellent housekeeper who reads this would like to ask Professor Henry [head of the board] what kind of lamp chimneys he has found to be the most lasting and least liable to crack.

There is a printed book of one hundred and fifty-two pages specially devoted to “instructions and directions to light-keepers,” and in this they receive explicit commands not only for their daily duties, but for all possible or imaginable accidents and emergencies. The first article of these instructions announces the fundamental duty of the light-keeper: “The light-house and light-vessel lamps shall be lighted, and the lights exhibited for the benefit of mariners, punctually at sunset daily. Light-house and light-vessel lights are to be kept burning brightly, free from smoke, and at their greatest attainable heights, during each entire night, from sunset to sunrise;” and it is added that “the height of the flame must be frequently measured during each watch at night, by the scale graduated by inches and tenths of an inch, with which keepers are provided.” Finally, “All light-house and light-vessel lights shall be extinguished punctually at sunrise, and every thing put in order for lighting in the evening by ten o’clock A.M. daily.”

It would be tedious and take more space than we have to spare, to give even a bald list of all the tools and materials required in a first-class light-house. A glance over the index of the volume of directions shows that it contains instructions for cleaning, placing, removing, and preserving the lamp chimneys; for cleaning the lamps; for keeping the lantern free from ice and snow; for preserving the whiting, rouge powder, etc.; for using two or three dozen tools; for preserving and economically using the oil, filling the lamp, using the damper; for precautions against fire; “hot to trim the wicks;” and for dozens of other details of the light-keeper’s daily duties.

The keeper is required to enter in a journal (daily) all events of importance occurring in and near his tower, and also to keep a table of the expenditure of oil and other stores. Besides the officer who is district light-house inspector, and who may make his examinations at any time, there are experts called “lampists,” who pass from light to light, making needed repairs, and also taking care that the machinery of the light is in order, and that it is properly attended to by the keepers.

Friday, June 25, 2010

In a Fog

From “The Light-Houses of the United States” in Harper's New Monthly Magazine (Vol. 48, Dec. 1873 to May 1874):

From “The Light-Houses of the United States” in Harper's New Monthly Magazine (Vol. 48, Dec. 1873 to May 1874):Fog-signals, many of which are required at different points on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, are of several kinds. Some are steam-whistles, the sound of which is made deeper or louder by being sent through a trumpet; but the most effective is probably the Siren. This ingenious machine consists of a long trumpet and a steam-boiler. The sound is produced by the rapid revolution past each other of two flat disks pierced with a great number of small holes; a jet of steam under high pressure is projected against the disks, which revolve past each other more than a thousand times a minute; as the rows of small holes in the two disks come opposite each other, the steam vehemently rushes through and makes the singular and piercing noise which a Siren gives out. One of these machines, of which a drawing is given [above]; costs about $3500 complete, with its trumpet, boiler, etc.

Daboll’s trumpet is worked by an Ericsson engine, and requires no water for steam.

Daboll’s trumpet is worked by an Ericsson engine, and requires no water for steam.

From the 1893 Light-House Board Annual Report (note the vast quantities of fuel):

Fog Signals Operated by Steam or Hot-Air Engines

913. Tillamook Rock, Oregon.—The first-class siren, in duplicate, was in operation some 316 hours and consumed about 16 tons of coal.

914. Columbia River light-vessel No. 50, Washington.—The 12-inch steam whistle was in operation some 802 hours and consumed about 71 tons of coal.

969. Destruction Island, Washington.—The first-class steam siren, in duplicate, was in operation some 825 hours and consumed about 49 tons of coal.

970. Cape Flattery, Washington.—The 12-inch steam whistle, in duplicate, was in operation some 520 hours and consumed about 32 tons of coal and about 100 feet of wood.

974. Point Wilson, Washington.—The 12-inch steam whistle was in operation some 157 hours and consumed about 16 tons of coal.

980. West Point, Washington.—The Daboll trumpet was in operation some 195 hours and consumed about 2 tons of coal and about 76 feet of wood.

982. Robinson Point, Washington.—The 12-inch steam whistle was in operation some 56 hours and consumed about 5 tons of coal.

1011. Turn Point, Washington.—The Daboll trumpet was in operation some 54 hours and consumed about 1 ton of coal.

1012. Patos Islands, Washington.—The Daboll trumpet was in operation some 90 hours and consumed about 1 ton of coal.

914. Columbia River light-vessel No. 50, Washington.—The 12-inch steam whistle was in operation some 802 hours and consumed about 71 tons of coal.

969. Destruction Island, Washington.—The first-class steam siren, in duplicate, was in operation some 825 hours and consumed about 49 tons of coal.

970. Cape Flattery, Washington.—The 12-inch steam whistle, in duplicate, was in operation some 520 hours and consumed about 32 tons of coal and about 100 feet of wood.

974. Point Wilson, Washington.—The 12-inch steam whistle was in operation some 157 hours and consumed about 16 tons of coal.

980. West Point, Washington.—The Daboll trumpet was in operation some 195 hours and consumed about 2 tons of coal and about 76 feet of wood.

982. Robinson Point, Washington.—The 12-inch steam whistle was in operation some 56 hours and consumed about 5 tons of coal.

1011. Turn Point, Washington.—The Daboll trumpet was in operation some 54 hours and consumed about 1 ton of coal.

1012. Patos Islands, Washington.—The Daboll trumpet was in operation some 90 hours and consumed about 1 ton of coal.

Tuesday, June 15, 2010

Keepers of the Song

From the June 13 Metropolitan Diary in the New York Times

Yo ho, Here's a tale

That's fair and dear to the hearts of those that sail

'Bout a lighthouse keeper and his bare faced wife

Who joined together for a different life

Yo ho, The winds and water tell the tale

My father was the keeper of the Eddystone light

He married a mermaid one fine night

From this union there came three

A porpoise and a porgy and the other one me!

Yo ho ho, the wind blows free,

Oh, for the life on the rolling sea!

Late one night, I was a-trimming of the glim

While singing a verse from the evening hymn

A voice on the starboard shouted "Ahoy!"

And there was my mother, a-sitting on a buoy.

Yo ho ho, the wind blows free,

Oh, for the life on the rolling sea!

"Tell me what has become of my children three?"

My mother she did asked of me.

One was exhibited as a talking fish

The other was served on a chafing dish.

Yo ho ho, the wind blows free,

Oh, for the life on the rolling sea!

Then the phosphorous flashed in her seaweed hair.

I looked again, and me mother wasn't there

A voice came echoing out from the night

"To Hell with the keeper of the Eddystone Light!"

The below video has the song as done by The Weavers, and scrolling lyrics rife with errant homonyms.

After showing an apartment to a prospective buyer, I walked east on 11th Street to return to my office. Two men were walking toward me, engaged in conversation, and as we passed each other, I heard these words:The Eddystone Light

“My father was the keeper of the Eddystone Light.”

Slowly the words began to register, and when I was a few paces past them, I turned and said, loud enough to make sure they could hear,

“And he married a mermaid one fine night.”

The men slowed. One of them turned, looked at me with a cautious expression and responded,

“From this union there came three.”

To which I replied, with the last line of the first verse of this old sea chantey,

“A porpoise, a porgy and the other was me!”

We both started laughing, introduced ourselves and compared notes on our introduction to this song.

Mine was from my old folk music days and his, more appropriately, sung on the ships he tended in the merchant marine.--Michael Raab

Yo ho, Here's a tale

That's fair and dear to the hearts of those that sail

'Bout a lighthouse keeper and his bare faced wife

Who joined together for a different life

Yo ho, The winds and water tell the tale

My father was the keeper of the Eddystone light

He married a mermaid one fine night

From this union there came three

A porpoise and a porgy and the other one me!

Yo ho ho, the wind blows free,

Oh, for the life on the rolling sea!

Late one night, I was a-trimming of the glim

While singing a verse from the evening hymn

A voice on the starboard shouted "Ahoy!"

And there was my mother, a-sitting on a buoy.

Yo ho ho, the wind blows free,

Oh, for the life on the rolling sea!

"Tell me what has become of my children three?"

My mother she did asked of me.

One was exhibited as a talking fish

The other was served on a chafing dish.

Yo ho ho, the wind blows free,

Oh, for the life on the rolling sea!

Then the phosphorous flashed in her seaweed hair.

I looked again, and me mother wasn't there

A voice came echoing out from the night

"To Hell with the keeper of the Eddystone Light!"

The below video has the song as done by The Weavers, and scrolling lyrics rife with errant homonyms.

Friday, June 11, 2010

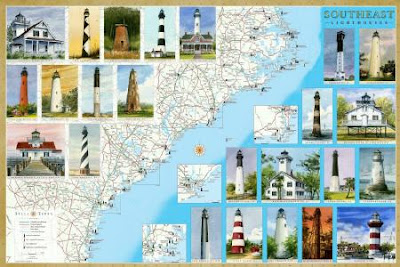

New Lighthouse Maps Cover the Southeast Coast from North Carolina to Florida

We're pleased to announce our latest maps and guides to Lighthouses: Florida and Southeast. The Southeast map covers North Carolina, including the Outer Banks, South Carolina and Georgia.

We're pleased to announce our latest maps and guides to Lighthouses: Florida and Southeast. The Southeast map covers North Carolina, including the Outer Banks, South Carolina and Georgia. Between them, the two maps locate and describe all the standing and lost lighthouses along about 2000 miles of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts.

In addition to the detailed cartography, each map features original watercolor illustrations, descriptions and history of every lighthouse, along with directions to the lighthouses or the best viewing spots.

The maps include directories of lighthouse and maritime museums, ferries, sightseeing cruises and flights.

The maps include directories of lighthouse and maritime museums, ferries, sightseeing cruises and flights.

They are available as folded maps to guide you in your travels, and as laminated posters.

In addition to the detailed cartography, each map features original watercolor illustrations, descriptions and history of every lighthouse, along with directions to the lighthouses or the best viewing spots.

The maps include directories of lighthouse and maritime museums, ferries, sightseeing cruises and flights.

The maps include directories of lighthouse and maritime museums, ferries, sightseeing cruises and flights.They are available as folded maps to guide you in your travels, and as laminated posters.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)